How to Report on Political Slime

Even in a presidential election race deplorable for personal attacks and vulgar language, the exchange about the candidates’ wives seemed to be a low point.

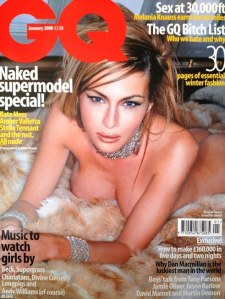

Before the Utah Republican caucuses on March 22 a Super PAC supporting Ted Cruz ran Facebook ads with a photo of Donald Trump’s wife Melania posing in the nude, with the caption: “Meet Melania Trump. Your Next First Lady. Or, You Could Support Ted Cruz on Tuesday.” (Cruz won the voting, 69 percent to Trump’s 14 percent.)

Donald Trump fired back with a tweet threatening to “spill the beans” about Cruz’s wife Heidi:

Lyin’ Ted Cruz just used a picture of Melania from a G.Q. shoot in his ad. Be careful, Lyin’ Ted, or I will spill the beans on your wife!

Journalists gleefully took to social media, airwaves, and websites of reputable print and broadcast news organizations to cover the latest brawl involving Donald Trump.

The Trump-Cruz tussle continued on Twitter and with sound bites throughout the week. Cruz taunted, “Donald, if you try to attack Heidi, you’re more of a coward than I thought.” Trump responded with a retweet depicting a glamorous Melania side-by-side a scowling Heidi with the line, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Cruz came back with more: “Donald, real men don’t attack women,” and “Donald, you’re a sniveling coward, and leave Heidi the hell alone.”

The War Over the Wives was extraordinary, albeit perverse, political theater. But was it news, deserving of coverage by journalists? Should the personal lives of politicians and their families be off limits? The answers to these questions are not as simple as we may like.

Undoubtedly, the right to privacy must be respected by journalists. However, exceptions can and should be made when there is an overwhelming public interest. President Bill Clinton’s private life could not be considered off limits in his “inappropriate relationship” with a 22-year-old White House intern. It illustrated several failings of legitimate interest to the public, from predatory sexual behavior and lack of sound judgment of the commander in chief to dishonoring America’s highest office.

Another exception is when public figures willingly remove the curtain of privacy, including the one around their families. The glamour image in the pro-Cruz ad came from a photo shoot published in 2000 by British GQ, when 30-year-old Melania Knauss of Slovenia was Trump’s fashion-model girlfriend (they were married five years later). According to the magazine, the photo shoot—with Melania “wearing handcuffs, wielding diamonds, and holding a chrome pistol”—took place on Trump’s customized Boeing 727.

Though tasteless and opportunistic—well, slimy—the pro-Cruz ad, sponsored by the Make America Awesome political action committee, touched on a reasonable question concerning Trump’s lifestyle choices. With Trump loudly questioning the values of entire communities—Mexicans and Muslims, for example—his own values are certainly fair game.

Trump’s retort—as tacky, bullying, and slimy as it was—also touched on a valid issue. The “beans” appeared to refer to Heidi Cruz’s bout with depression a decade ago—including an incident that has been reported by the New York Times among others.

In 2005, after Heidi quit a post at the White House to be reunited with her public-servant husband in Texas, police responding to a 911 call reportedly found Heidi sitting next to an expressway with her head in her hands. An officer’s report later stated: “I believed that she was a danger to herself.”

The personal background of a prospective First Lady is of legitimate interest to voters. This is especially reasonable in this case, given that Heidi Cruz has played an active public role campaigning and raising money in her husband’s quest for the White House. (It can also be noted that the Cruz campaign has used their young children as cuddly props in political ads, promoting the image of Cruz as a stable family man.)

So it’s difficult for journalists to ignore personal attacks like the Cruz-Trump exchanges when the attacks relate to issues of public interest. The question is how to appropriately report on the slime-slinging.

Huffington Post came up with an idea in mid-2015. The editors felt that the Trump campaign was a “sideshow,” to be expected from a self-promoting tycoon who had made a second career as a reality TV star.

So Huffpost announced it would cover Trump’s campaign in the Entertainment section rather than as part of its political coverage. “If you are interested in what The Donald has to say, you’ll find it next to our stories on the Kardashians and The Bachelorette,” the editors said in a note to readers. By December, with Trump blowing away the rest of the Republican field for six consecutive months, it became clear this was not the answer, and Arianna Huffington herself announced a change in plan. “We will no longer be covering his campaign in Entertainment,” she told readers. It has “morphed into something else: an ugly and dangerous force in American politics.”

In a column in The Fix, Washington Post writer Callum Borchers suggests making a clear distinction between remarks related to policy and those that are not:

When Trump says he will deport every last undocumented immigrant living in the United States, the media have to cover the statement extensively because it’s about what he plans to do as president. There are serious questions to answer: Is the proposal realistic? What would it cost? How would it affect the economy? What would it do to America’s image?

When Trump says he will “spill the beans” on Cruz’s wife, however, the media response should be much more muffled. Not silent—you can’t just pretend he never said it or that Cruz never responded—but there’s not really substance to dissect. The sole purpose of a comment like that is to steal airtime and ink that might otherwise be devoted to issues that actually matter.

That’s a start, but journalists need to go further. The massive media attention given to Trump’s outbursts and the personal attacks exchanged by candidates is part of the deeper problem of the horse race coverage of American politics. That’s the gallop of 24/7 coverage highlighting controversial comments, gaffes, petty squabbles, personality clashes, and opinion polls that overtakes coverage of substantive issues. It’s a problem that has become even greater in the digital media age, where journalists’ reports are left competing with the endless chatter and diatribes on cable shows and social media not to mention the propaganda output of political organizations.

Part of the solution is to double-down on packaging and framing of political coverage that is worthy of the press’s role in a democracy. The professional news media needs to keep the focus overwhelmingly on the serious issues of the day and the candidates’ positions on them, and not get sucked into the vortex of sensational tweets and sound bites. Slime sells, so this is an important test for news media establishments hungry for ratings, web traffic, and profits.

When matters like a candidate’s values or personal lifestyle do become a legitimate public interest, the media should report on this in a measured, thorough, and responsible manner. The coverage should be kept in proper proportion to the coverage of other public concerns, such as the candidates’ positions on pressing domestic and foreign policy issues. The character of politicians who revel in slime tactics should also receive appropriate scrutiny.

One thing we saw again in the War Over the Wives is the pitiful state of political discourse in a nation to which the world looks for leadership. That’s a story worth covering.

—Scott MacLeod